Navigating Tax Strategies in a High-Interest Rate Environment: Considerations for Non-Resident Investors in Canada

Prepared by Danny Guérin, Myriam Vallée and Justine Lambert, Andersen in Montreal (Canada)

INTRODUCTION

The significant surge in inflation throughout 2022 has been a predominant concern for the economic community and the government alike as the inflation averaged 6.8%, reaching a peak of 8.1% in June of 2022[1] However, the implemented tightening of monetary policy appears to have yielded results in Canada, as inflation averaged 3.9% in 2023.[2] Entering 2024, the Canadian economy might persist in a recessionary phase, influenced by the delayed effects of increased interest rates.

This current economic landscape, coupled with high-interest rates, has prompted foreign investors to reassess their tax strategies concerning their investments in assets and the financing of their subsidiaries within the country. The prevailing high-interest rates impact investment returns and financing costs, creating a dynamic environment that necessitates a thorough evaluation of existing tax structures. As global economic conditions evolve, foreign investors are increasingly inclined to recalibrate their approaches to optimize tax efficiency with a view of minimizing the cost of capital.

This document will offer insights into the sections of the Income Tax Act[3] (“ITA”) that non-resident investors should be aware of when engaging in investments within Canada considering the current elevated interest rates.

Unless otherwise indicated, any reference to a provision refers to the ITA. Furthermore, for the purposes of this paper, the examination of pertinent ITA provisions will be confined to their application from an inbound perspective i.e. when a non-resident entity holds investments in Canada.

UPSTREAM LOAN – DEBT TO A NON-RESIDENT FROM A CANADIAN CORPORATION

A non-resident (hereinafter “NR“) corporation that owes sums of money or is indebted to a Canadian corporation can face serious tax consequences, especially if the debt does not bear interest. In the current economic landscape, what is considered a reasonable interest rate (as well as the prescribed rates applicable in certain situations according to the ITA) is notably high and can result in tax liability under specific circumstances. Several provisions exist regarding any advantages provided to a NR such as postponing loan repayments to Canadian subsidiaries, low or interest-free loans or other benefits.

Shareholder Debt Provisions – Subsection 15(2)

From an inbound perspective, subsection 15(2) of the ITA is intended to prevent the avoidance of withholding taxes through “disguised” repatriation of funds from a Canadian corporation to its NR shareholders through unpaid upstream loans or other transactions resulting in the shareholder incurring debt to the Canadian corporation. Subsection 15(2) may also be relevant to a loan or debt issued by a Canadian creditor to a NR corporation that does not deal at arm’s length with, or is affiliated with, a shareholder of the creditor.

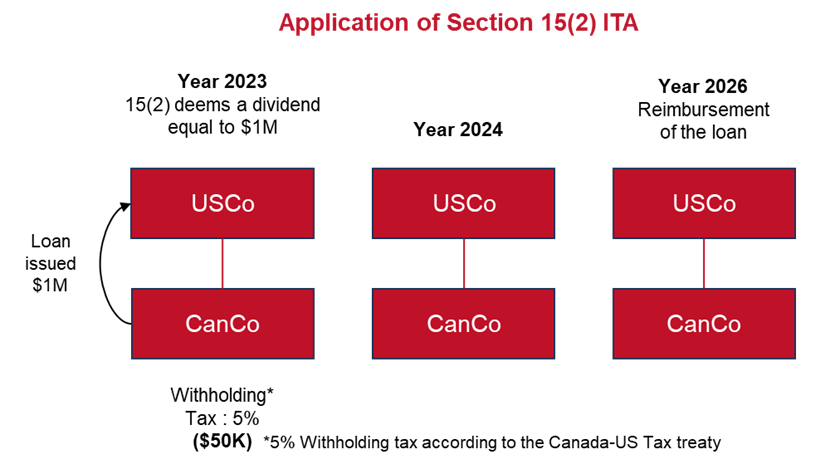

In cases where the provision is applicable, the principal amount of the loan or debt is deemed to have been paid to the NR taxpayer as a dividend from the Canadian creditor.[4] Consequently, this dividend becomes subject to a 25% Part XIII tax (subjects to treaty benefits applicable under the treaty section dealing with dividends). For example, under the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty, the Canadian domestic withholding tax rate of 25% as determined under subsection 212(2) of the ITA could be reduced, upon treaty eligibility, down to 5% in certain instances).[5] The Canadian corporation must withhold and remit tax on the borrower’s behalf pursuant to subsection 215(1).

Subsection 15(2) could be avoided where the loan or indebtedness is repaid within one year after the end of the taxation year of the lender or creditor in which the loan was made or the indebtedness arose.[6] Such repayment must not be part of a series of loans or other transactions and repayments, for instance, where a loan is settled shortly before the year-end, and a similar or substantially equivalent amount is borrowed shortly after the year ended. Cash pooling arrangements might fall within the definition of a series of loans or other transactions and repayments. Nevertheless, the current economic landscape, characterized by inflationary pressures, and volatile markets, could impede the ability to repay debts within this period.

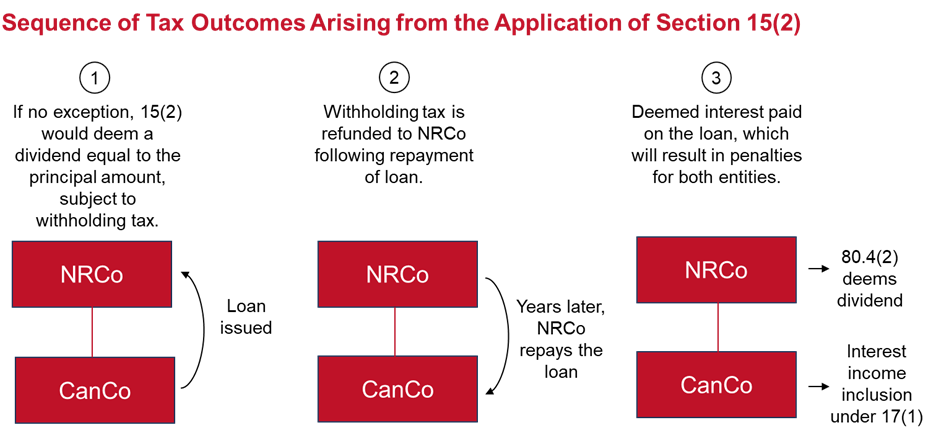

Subsection 227(6.1) of the ITA also allows for a refund of Part XIII tax, withheld and remitted, if the NR later repays the loan or indebtedness (totally or partially) and the NR request a refund of the withholding taxes paid within two years following the end of the calendar year during which the loan in question was repaid, provided that the repayment was not, as mentioned above, made as part of a series of loans or other transactions and repayments.

Pertinent Loans or Indebtedness (PLOI) – Subsection 15(2.11)

To avoid the application of subsection 15(2) and related withholding tax implications, a Canadian lender (Corporation Resident in Canada “CRIC” or qualifying Canadian Partnership) and a NR borrower (NR “subject corporation” which controls the CRIC or does not deal at arm’s length with a subject corporation controlling such CRIC) could also jointly designate a loan from the Canadian lender as a PLOI. When a valid PLOI election is executed, the provisions of subsection 15(2) no longer apply to impute a dividend to the NR shareholder, but the Canadian entity becomes subject to an annual interest inclusion as outlined in section 17.1 of the ITA.

The interest income for the year, pursuant to subsection 17.1(1), is the greater of:

- The calculated interest at a prescribed rate[7] on the amount owed; and

- The actual amount of interest reported as income by the Canadian lender for the year related to the PLOI.

Subtracting any interest payments already accounted for in the lender’s total income from interest payments made by the debtor.

Determining the worthiness of using the PLOI election for a specific cross-border shareholder loan requires evaluating various factors. This includes comparing the tax implications of Canadian withholding tax on a subsection 15(2) income inclusion versus Canadian income tax on imputed interest income under subsection 17.1(1). Additionally, assessing loan terms, such as whether it accrues interest, the repayment schedule, and the availability of foreign tax credits for the NR debtor, is crucial.

The outcomes of a PLOI election are significantly influenced by the prescribed rate, which in turn depends on the economic situation. Currently, choosing the PLOI has become less attractive due to its exceptionally high prescribed interest rate, reaching 9.16% in the first quarter of 2024.

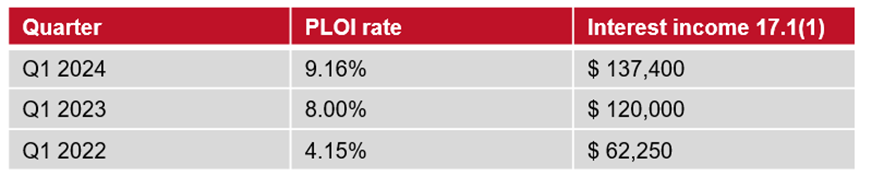

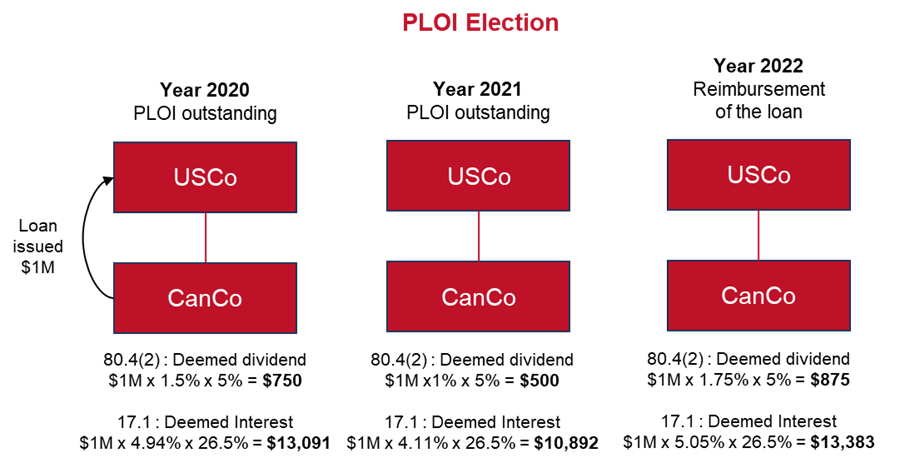

The following table represents an evolution of the interest income inclusion pursuing a PLOI election on an outstanding loan of $ 1,500,000. It should be noted that for simplicity purposes, the PLOI rate of the first quarter of each year was used to calculate the yearly interest to impute on the example below, even though such would technically need to be computed quarterly. Additionally, section 80.4 of the ITA (explained later in this paper) could also apply to a PLOI.

Benefit to a Shareholder – Subsection 15(1)

Subsection 15(1) establishes a general rule stipulating that any benefits provided by a corporation to its shareholder are to be included in the shareholder’s income, without a corresponding deduction in the corporation’s income. This provision is designed to encompass situations where wealth is distributed to a shareholder without triggering tax, provided it is not already addressed by another provision. Similar to 15(2) and from an inbound perspective, it prohibits the tax-free repatriation of wealth or surplus to a NR shareholder. The benefit is then taxed as a deemed payment in respect of property, services or otherwise depending on the nature of the benefit.[8] Note that subsection15(1) only applies to a direct shareholder of the corporation.[9]

Deemed Interests Paid and Received

Income Inclusion Related to an Amount Owed by a NR – Subsection 17(1)

Subsection 17(1) of the ITA is an imputed interest rule that applies when a NR corporation owes an amount to a Canadian-resident corporation (regardless of its relationship with the creditor), the unpaid balance has continued for an uninterrupted period exceeding 12 months, and no interest (or interests income computed at a rate below the prescribed rate) has been included in the Canadian corporation’s taxable income. If 17(1) applies, the prescribed rate[10] will be used to calculate a deemed interest for the Canadian corporation.

The purpose of this provision is to prevent Canadian corporations from avoiding or deferring Part I tax payable by extending credit to a NR and not including interest income in its revenue, or an interest that is not computed in reference to a reasonable rate (i.e. leaving untaxed funds offshore).[11] The reasonableness of an interest rate is not defined in the ITA. It is a factual evaluation that can only be determined by assessing the economic circumstances of a particular commercial arrangement and the credit worthiness of the debtor. Such rate could be lower than the prescribed rate, but cannot be a nil rate.[12] However, if 17(1) applies and is being invoked by the tax authorities, the prescribed rate will be used in the calculation of the resident corporation’s imputed interest income. The prescribed rate in the case of interest-free and low-interest loans reaches 6% in the first quarter of 2024.

Unlike subsection 15(2), subsection 17(1) does not require that entities be related.

Furthermore, 17(1) does not apply in respect of an amount owing to a corporation resident in Canada by a NR person if a tax has been paid under Part XIII on the amount owing by application of 15(1) or 15(2).[13] Therefore, if a refund of withholding tax is received because of the repayment of indebtedness by the NR corporation, the Canadian-resident corporation could have a tax liability related to the amount that should have been imputed in the income in prior taxation years under 17(1). This could further result in penalties and interests (i.e. from unpaid income taxes relating to previous years additional interest income inclusion by the Canadian corporation).

Imputed Interest Benefit for a NR Debtor – Subsection 80.4(2)

Where a NR corporation is a shareholder (or is not dealing at arm’s length with a shareholder)[14] of a Canadian corporation, and by virtue of that shareholding, received a loan from, or otherwise incurred a debt to, that corporation, the NR corporation is deemed to have received a benefit in a taxation year equal to the difference between interest actually paid within the financial year (or by 30 days after the financial year-end) and interest computed at the prescribe rate on the outstanding balance. The prescribed rate is the same as for the application of 17(1), namely 6% in the first quarter of 2024. The benefit is considered a deemed dividend and is subject to the withholding tax provided by the Part XIII.

The calculation of the benefits with the prescribed rate is made daily to the outstanding loan balance (it is not a requirement for a loan balance to remain outstanding at the year-end for the benefit to be computed). If the loan or debt is entirely repaid before the year concludes, the benefit is calculated based on the number of days in the year during which the loan was outstanding.

The benefit is considered under subsection 80.4(2) a deemed dividend issued by the resident corporation to the NR taxpayer and will be subjected to Part XIII withholding tax (25% – potential rate reduction provided by treaty benefits are available).[15]

However, 15(2) has priority over 80.4(2) and the latter won’t apply if the loan or indebtedness has already been included in the taxpayer’s income under 15(2).[16] Thus, similarly than with subsection17(1), if a refund of withholding tax is received because of the repayment of indebtedness by the NR corporation, a potential withholding tax liability and related penalties and interests might be triggered due to the benefit that should have been imputed in the income of prior taxation years under 80.4(2).[17]

As outlined in the table above, it is crucial to highlight that subsection 80.4(2) may be applied concurrently with subsection 17(1).

Overview of Transfer Pricing Rules – Subsection 247(2)

Canada’s regulations on transfer pricing require that transactions between a taxpayer and a non-arm’s length NR entity adhere to typical terms of transactions between unrelated parties. Moreover, Canada’s tax treaties, often in alignment with Article 9, may allow adjustments to be made based on the arm’s-length terms. The ITA does not prescribe a specific transfer pricing method for taxpayers; the Canada Revenue Agency (“CRA”) advocates for the approach recommended by the OECD’s[18] “Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations”.

Section 247, particularly through its paragraph (2), does not levy taxes; instead, it adjusts the amount or characteristics of any determinations made for Act-related purposes. This includes calculating taxes owed under Part I or any other section of the Act, including Part XIII (withholding tax on income from Canada paid to a NR).

Transfer pricing rules apply to interest rates on loans, whether upstream or downstream, between a Canadian corporation and its NR parent corporation or a non-arm’s length NR entity.[19] Thus, it could apply in conjunction with other provisions of the ITA regarding interest rates. As per subsection 247(2.1), adjustments made under transfer pricing rules take precedence over other ITA provisions, such as subsections 17(1) or 18(4). The adjustment is thus considered in determining the application of these other provisions.

Any loans or indebtedness to a NR (shareholder or persons connected to such) within a multinational group must be thoroughly examined to ensure it carries a reasonable interest rate, thereby mitigating the risk of triggering the application of subsections 247(2), 17(1) or 80.4(2), given the significant increase in interest rates in Canada in recent years.

Where subsection 15(2) has already applied in the case of an indebtedness that was not bearing interest and provided that the indebtedness has been subsequently repaid, a NR corporation should proceed carefully regarding the possible refund of Part XIII tax as it could result in a potential tax liability from the retroactive application of subsection 17(1) or 80.4(2).

Furthermore, it should be noted that even though a PLOI election is available to avoid tax consequences under 15(2) on an interest free loan or a loan issued at an unreasonable interest rate, higher prescribed rates from the current economic condition must be factored in, and calculations should be made to compare tax implications of a deemed dividend under 15(2) with those of a PLOI election.

In the below contemplated situation, CanCo would issue a $1M loan to USCo during the year 2023 and the loan would not bear interest. Let’s also assume that the loan would be reimbursed in 2026. Thus, it would not be reimbursed within one year after the end of 2023, meaning that the subsection 15(2.6) exception would not be available to avoid the application of 15(2). The provision would then deem a dividend paid by CanCo to USCo of the value of the loan ($1M), to which withholding taxes would have to be withhold by CanCo ($50K).

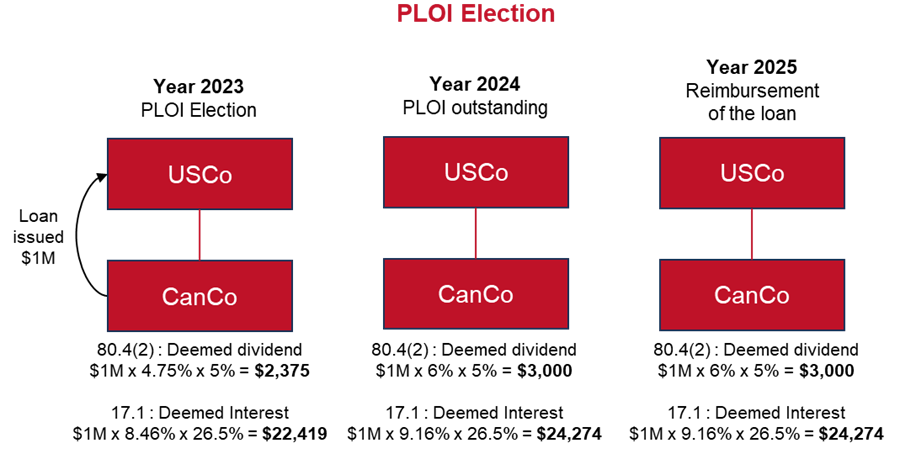

In comparison, should a PLOI election be made regarding the same interest free loan as the previous example to avoid the application of 15(2), subsection 80.4(2) would deem a dividend paid by CanCo to USCo equal to the interests that should have been paid on the loan calculated at the prescribed rate each year. In addition, the PLOI election would impute an interest income to CanCo calculated at the PLOI prescribed rate until the loan would be reimbursed under 17.1. The current scenario underscores the potential diminished value of a PLOI election (total estimated 80.4(2) and 17.1 costs of close to $80K) compared to allowing the provisions under 15(2) to take effect which would result in a $50K WHT, given the elevated interest rates stemming from the existing inflationary economic conditions.

In a scenario where the same interest-free loan would have been issued in 2020, the appeal of a PLOI election would have been markedly different. The tax implications arising from such an election would have been far less punitive due to substantially lower prescribed rates. Therefore, it would have been in the advantage of the taxpayer to opt for a PLOI election (total estimated 80.4(2) and 17.1 costs of close to $40K) and avoid the application of subsection 15(2) withholding tax of $50K.

Cash Pooling Arrangements and Tax Considerations

Cash pooling is a treasury management tool that allows related subsidiaries within large corporations to manage their daily working capital fluctuations. However, when it comes to foreign multinational entities with Canadian subsidiaries, taking full advantage of cash pooling can be challenging due to restrictive Canadian tax rules and rising interest rates.

There are two types of cash pooling arrangements: physical and notional. Although both might seem economically alike, their tax treatments are different from a Canadian tax perspective.

Physical cash pooling arrangements involve the physical movement of funds from the bank accounts of the participating members to the central account held by the leader of the cash pool, acting as a financing corporation, with the objective of consolidating available liquidity into a single master account.

The movement of cash could result in intragroup balances between the participating members and the entity serving as the financing corporation, and hence could be subjected to the provisions previously addressed.

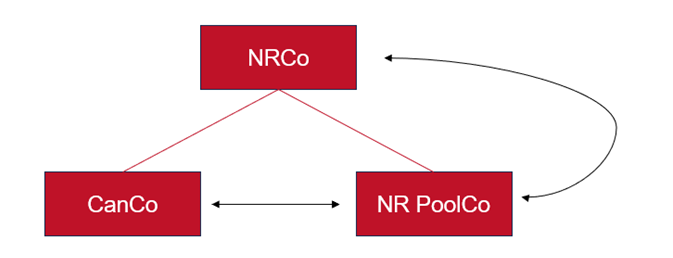

In the following situation, a Canadian corporation (“CanCo”) is a subsidiary of a NR corporation (“NRCo”). NRCo, CanCo and other subsidiaries have entered into an actual centralized cash management agreement, under which a clear agreement establishes the lender-borrower relationship between each of the companies. CanCo has excess cash and NRCo needs to borrow to meet its liquidity requirements. CanCo therefore lends the funds to the NR entity serving as the financing corporation (“PoolCo”) which, in turn, lends the funds to NRCo. None of the loans bears interest.

It should be noted that each loan granted by CanCo to PoolCo must be analyzed separately, and that loans receivable and payable cannot be netted for the purposes of determining the application of subsection 15(2).[20] Because PoolCo is a subsidiary of Canco’s shareholder, NRCo, 15(2) would apply to the loans, deeming a dividend paid by Canco to PoolCo, on which Part Xlll withholding tax would apply. Besides, because PoolCo is not a shareholder of CanCo, some treaty benefits reducing the amount of withholding taxes might not be available.[21]

Typically, in a physical cash pooling arrangement, the loans are repaid within less than one year after the creditor’s year-end, which could prevent the application of subsection 15(2). However, it could be considered a series of loans, repayments, or other transactions, and given the numerous deposits and withdrawals of funds, it may be difficult to distinguish what is part of a series of loans, repayments, or other transactions from what constitutes a final repayment. The CRA could accept the use of the first-in, first-out technique to track loan repayments, but determining if a transaction is part of a series of loans, repayments, or other transactions can only be made following an exhaustive analysis of all the relevant facts and circumstances.[22]

A PLOI election could be made so that subsection 15(2) does not apply, however, as previously mentioned, due to the prevailing high interest rates, the attractiveness of making a PLOI election is currently diminished.

In the scenario outlined above by this example, if subsection 15(2) does not apply, subsection 80.4(2) might be relevant because of the lack of interest on the liquidity lent by CanCo to PoolCo. This would result in a benefit being conferred to PoolCo and taxed as a deemed dividend, subject to Part XIII withholding tax. Furthermore, subsection 17(1) may also impute interest income calculated at the prescribed rate to CanCo’s income if PoolCo remains in a debtor position for more than 12 consecutive months.[23]

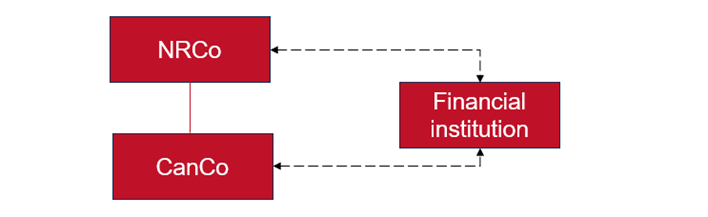

In contrast, a notional cash pooling arrangement involves a purely virtual reconciliation of bank account balances, and no cash if physically moved to another entity. Each entity of the arrangement maintains its own cash balances and deals directly with the financial institution, who will determine the companies’ borrowing capacity and the interest rate paid (or to be paid). The financial institution is often granted authorization to reconcile negative overdraft balances by utilizing positive deposit balances.

However, the back-to-back rules, which will not be addressed in the present paper, prevent the insertion of a third party between the Canadian lender and the foreign borrower to circumvent the application of subsection 15(2)[24]. These rules could catch certain cash pooling arrangements. Back-to-back rules are also relevant for the application of subsections 17(1), 80.4(2), thin capitalization rules (discussed later in this paper) and could apply as well in certain notional cash pooling arrangements.[25]

Regarding cash pooling arrangements, the CRA has not yet adopted any general positions and there are currently no clear administrative policies preventing the CRA from applying subsection 15(2) to a cash pooling arrangement (either physical or notional). Each arrangement needs to be analyzed based on its specific facts and circumstances, and every individual transaction needs to be broken down.

Debt Forgiveness by the Canadian Corporation Creditor

In the current global economic climate, a Canadian corporation (“CanCo”) having loaned an amount to a NR entity (“NRCo”) may find itself in a position where the only option left (and the better approach to take from a multinational group’s perspective) would be to consider forgiving such debt, particularly if the NR debtor is facing financial difficulties. This business decision could be motivated by various factors, such as financial challenges, fostering goodwill, or adapting to evolving market conditions. Depending on the circumstances leading to the debt write-off, particularly if the debtor is insolvent, such debt forgiveness could potentially trigger a capital loss for the Canadian lender. For a Canadian debtor, this could result in the application of the section 80 (“debt forgiveness rules”) regarding a debtor’s gain on settlement of debt (discussed later in this paper).

To forgive or write off a debt can sometimes trigger a deemed disposition of the debt for Canadian tax purposes. If such debt qualifies as an uncollectible debt (or debt that was established by the creditor to have become a bad debt during the year) and a valid election under subsection 50(1) is filed on time (triggering a deemed disposition of the debt receivable at the end of that year for proceeds equal to nil and a reacquisition of the debt immediately thereafter at a cost equal to nil), the Canadian creditor could realize a capital loss on the debt.

However, the loss may not be claimable if the debt was not acquired by the taxpayer for the purpose of earning income from a business or property.[26] This scenario could occur if the debt did not bear interest and is owed by a NR shareholder or a NR corporation not dealing at arm’s length with a shareholder of the creditor. Therefore, the capital loss on the disposition of the debt could be deemed to be nil.[27]

If the debtor is not insolvent and the 50(1) election is unavailable, the cancellation of the debt (i.e. debt being legally settled) results in the debt being deemed to have been disposed of in favor of the debtor.[28] In that case, even when a debt was acquired for the purpose of earning income from a business or property, there remains a risk that the Canadian Revenue Agency (“CRA”) may invoke subparagraph 69(1)(b)(i), which provides that if a taxpayer sells anything to a non-arm’s length individual for less than its fair market value, the taxpayer is deemed to have received consideration equal to that fair market value. Consequently, the CRA could argue that the fair market value of the disposed debt is higher than what the taxpayer believes, leading to the rejection of the loss claimed on the debt receivable disposition.

If a Canadian creditor opts to pardon a loan or debt owed by a foreign shareholder debtor, and if the said loan or debt hasn’t been previously included into the income of the debtor under subsection 15(2) due to a PLOI election, this could lead to the application of subsection 15(1), as the forgiven amount could be considered a benefit for the shareholder and be subjected to withholding tax.[29]

However, when it comes to a loan or debt owed by a foreign debtor who is not a shareholder of the Canadian creditor, the amount would probably not fall within the scope of subsection 15(1), as this provision only applies to a shareholder of the Canadian creditor. Additionally, 15(2) would not apply to the forgiven amount, the PLOI election having removed the loan from its application in the taxation year in which the loan or indebtedness was incurred. Regarding subsection 17.1(1), the pardoning of the PLOI would put an end to any imputation of interest since the outstanding amount is now nil.

The ITA does not provide any mechanism or specific provision to subject the forgiven amount to a withholding tax when the amount is due to a NR corporation that is not the shareholder of the Canadian creditor. The taxpayer should act with caution in such situations as the CRA could explore alternative provisions like the General Anti-Avoidance Rule (“GAAR”) application, subsection 56(2) [Indirect payments], or 246(1) [Benefit conferred on a person].

DOWNSTREAM LOAN – DEBT TO A CANADIAN CORPORATION FROM A NON-RESIDENT

High interest rates in Canada, coupled with an impending recession, may affect the profitability of a Canadian subsidiary. With financing costs significantly increased, a NR parent corporation will need to contemplate restructuring to mitigate the impact of specific provisions and safeguard the subsidiary’s tax flow.

Payment of Interests – General Rules

Interests paid or accrued in relation to a loan or debt (i.e. pursuant to a legal obligation to pay interest) borrowed for the purpose of generating income by a Canadian corporation is generally deductible from the Canadian corporation’s taxable income.[30] If such interest is payable to a NR creditor, a withholding tax on the interest payment made to the NR creditor of 25% is applicable (from a Canadian domestic perspective).[31] However, several tax treaties have lowered the withholding tax rate to 10% or 15%. Yet, the Canada-US tax treaty provides that interest arising in Canada and beneficially owned by a resident of the US may be taxed only in the US (i.e. no withholding tax is applicable).[32]

Also, Canada does not impose withholding tax on interest payments to arm’s-length non-residents, subject to exceptions[33].

Limitation of Interest Deductibility

Overview of Thin Capitalization Rules – Subsection 18(4)

The thin capitalization rules restrict the tax benefits arising from financing a Canadian subsidiary by a NR by disallowing the Canadian corporation from claiming an interest deduction on interest-bearing debt owed to a “specified NR shareholder” (or a NR person not dealing at arm’s length with a specified shareholder) that surpasses a 1.5:1 debt-to-equity[34] ratio.

A “specified NR shareholder” is a NR shareholder who, either individually or collectively with other non-arm’s length persons, holds shares conferring 25% or more of the voting rights or of the fair market value of the Canadian corporation debtor.

When the debt surpasses a 1.5:1 debt-to-equity ratio, the corporation’s interest deduction is reduced based on the proportion of the excess debt to equity amount. The disallowed interest is then treated as a dividend[35] and becomes subject to withholding tax.

The thin capitalization rules also encompass specific back-to-back provisions designed to address loan structures that might attempt to evade such rules by using an arm’s length intermediary in a transaction between a Canadian subsidiary and its specified NR shareholder.[36]

When a NR corporation loans money, or otherwise finance a Canadian corporation subsidiary, the interest rate associated with the loan needs to comply with transfer pricing regulation[37].

In times of financial hardship, the equity of a particular Canadian corporation may be impacted. This will amplify the unwanted effects of thin capitalization rules, further limiting the ability of a NR parent corporation to efficiently leverage its subsidiary through debt. Injecting capital may be necessary to sustain the Canadian corporation’s business without triggering the thin capitalization rules.

Overview of the Excessive Interest and Finance Expenses Limitation (“EIFEL”) Regime (proposed 18.2 and 18.21 ITA)

The proposed EIFEL rules, stemming from the OECD’s BEPS initiative (action 4), aim to limit interest deduction and financing expenses (“IFE”) in specific instances. These rules will apply after considering the thin capitalization rules. The specifics of the proposed EIFEL regime are not covered in this paper; however, several key points are worth mentioning in broad strokes.

These rules establish a cap on IFE, typically at 30%[38] of adjusted taxable income, which refers to a corporation’s EBITDA[39] calculated for tax purposes. Canadian member of a group of corporations may opt for a joint election to use a group ratio. Disallowed net interest expenses become “restricted interest expense” carrying forward indefinitely under the proposed EIFEL regime.

IFE encompasses various expenses, including interest and financing costs, capitalized interest, and certain lease payments. Also, interest and financing revenues can offset IFE.

The EIFEL regulations won’t apply to certain excluded entities, such as small Canadian-controlled private corporations (“CCPC”) and their associated corporations, provided that their taxable capital employed in Canada is less than $50 million, as well as certain entities within a group with negligible foreign ownership and minimal operations or presence outside of Canada.

Just like thin capitalization rules, the EBITDA of a corporation is impacted by its economic and financial environment. Financial challenges for a corporation subjected to the EIFEL rules could lead to a heightened restriction on the ability of a NR parent to provide tax efficient debt financing to its subsidiary.

Guarantee From a Parent Corporation

During difficult economic periods, a NR corporation might have to provide a guarantee regarding a loan to its subsidiary. In this case, the guarantee fees imposed to the Canadian corporation will be subject to transfer pricing rules i.e. the fees must correspond to the amount that would be determined between arms-length entities.

The consideration for the fees is deemed to be payment of interest for the Part XIII withholding tax,[40] but for the application of the rest of the ITA, the guarantee is not considered a loan of an indebtedness whatsoever.

Income Additions for Unpaid Amounts – Section 78

Subsection 78(1) applies when certain deductible expenses, such as interest payments, are deducted in the Canadian corporation income on an accrual basis, but remains unpaid, the creditor being a non-arm’s length person. If the deducted amount remains unpaid at the end of the second year following the year during which the expense was initially incurred, 78(1) requires the amount to be included back into the income of the taxpayer for the third taxation year following the taxation year in which the expense was incurred.

To avoid having this subsection applied, the debtor and creditor can make an election under paragraph 78(1)(b) (Form T2047) which would deem the unpaid amount to have been paid, and then loaned back to the debtor on the first day of the borrower’s third taxation year.

However, the deemed payment of the unpaid amount could still result in a withholding tax if the interest is owed to a non-resident entity (other than a US shareholder of the debtor).

In the case of unpaid interests, the new “loan” won’t be considered as an “outstanding debt to specified NRs” for purposes of the thin capitalization rules. However, if these unpaid interests bear compound interest and those interests are paid and deductible as permitted under paragraph 20(1)d), the new “loan” would be considered as an “outstanding debt to specified NRs and could be subject to the thin capitalization rules.”[41]

Debt Forgiveness by the Non-Resident Creditor

A NR parent corporation may consider the option of waiving a debt receivable from its Canadian subsidiary, when such entity is facing financial difficulties, which in our current economic environment is not uncommon. For the Canadian debtor, proceeding with this option is not without consequences, as this could result in the application of section 80, which could ultimately lead to an income inclusion for the Canadian debtor.

Overview of Debt Forgiveness Rules – Section 80

Section 80 of the ITA refers to the rules governing debt forgiveness. For section 80 to apply, the debtor must have issued a commercial obligation, which includes a commercial debt obligation.

A commercial debt obligation is a debt obligation which bears interest, that is paid or payable by the debtor and deductible in computing the latter Canadian net income for tax purposes (or if no interest is paid or payable, such amount would have been deductible should interest had been applicable to the obligation in the first place). The definition of commercial debt obligation includes income bonds, debts relating to the acquisition of land or depreciable property, distressed preferred shares and any other debt obligation incurred for the purpose of earning income from a business or property. Debts incurred for personal purposes or for the purpose of earning tax-exempt income are not included.

For the debtor, a gain on the settlement of a debt would be “current” if related to day-to-day transactions, or “capital” in nature if related to capital transactions. Section 80 would only apply to a debt of a “capital” nature. When the forgiven debt is “current” in nature, the amount should be included in computing income for the taxation year under section 9 of the ITA.[42]

When a creditor settles (partially or completely) a commercial debt issued by a debtor (except for a bankrupt debtor), subsection 80(1) provides calculations of the forgiven amount[43] that could be included in the debtor’s income under 80(13) unless the debtor has sufficient tax attributes to shelter such income inclusion.

The law prescribes an order in which the tax attributes must be applied against the forgiven amount. Some of the attribute’s reductions below are mandatory while others are elective:[44]

- Non-capital losses (mandatory application and earlier losses are applied/reduced first);

- capital losses (mandatory application and earlier losses are applied/reduced first);

- capital cost to the debtor of a depreciable property that is owned by the debtor and the undepreciated capital cost to the debtor of depreciable property of a prescribed class (optional if designated on the prescribed form filed with the debtor’s income tax return);

- resource expenditures (optional if designated on the prescribed form filed with the debtor’s income tax return);

- adjusted cost bases of capital properties (optional if designated on the prescribed form filed with the debtor’s income tax return);

- etc.

If income inclusion occurs (having considered any potential transfer to eligible transferees of the unapplied portion of the forgiven amount), half of such unapplied portion would be included in a corporate taxpayer’s income (while 100% of such unapplied amount would be included into the income of a debtor that is a partnership). The debtor that is a corporate taxpayer can spread the income inclusion over a five-year period (such incentive is not available to debtors that are partnerships due to subsection 80(15)).[45]

Further, corporations resident in Canada throughout the year are permitted to claim a deduction that effectively limits their net income inclusion to twice their net asset value.[46] This ensures that the inclusion does not render the corporation insolvent. If the corporation is already insolvent, it simply won’t be required to recognize income under subsection 80(13).

However, the calculation of the net asset value won’t consider any amounts distributed in the 12-months period preceding the corporation’s year-end, such as cash dividends, reductions of paid-up capital, redemption, acquisition, or cancellation of shares, or any distribution or appropriation of property to a shareholder. The CRA also has the power to increase the reduction of a debtor’s tax attributes to diminish the income inclusion amount that is subject to a deduction. [47]

Forgiveness of debt and capital contribution

In the context of restructuration due to financial difficulties, many traps need to be avoided so that transactions would not be caught under the application of Section 80.

One of the available options for a taxpayer to clear off its debts when facing financial difficulties is the debt-to-equity conversion. In this situation, the debt owed is forgiven in exchange for shares to be issued by the debtor to the creditor. In that case, the debt would be deemed to have been forgiven at an amount equal to the fair market value (“FMV”) of the shares issued pursuant to paragraph 80(2)(g). If the taxpayer’s financial challenges do not significantly reduce its fair market value to a level below the debt itself (“under water” level), the issue of share valuation should not prove problematic. Moreover, creditors typically would not agree to convert commercial obligations into shares valued lower than the principal amount of the claim.

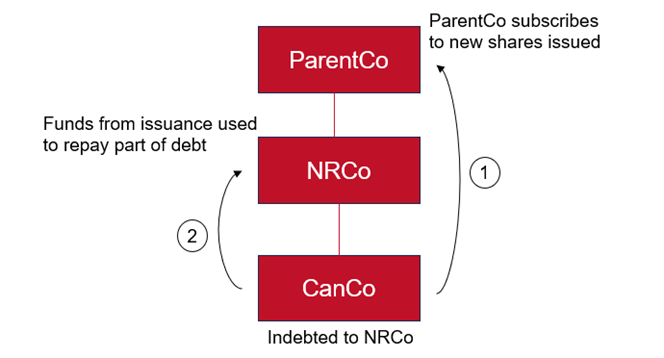

In the following scenario, CanCo owes a debt to its NR parent corporation. CanCo opts to issue shares to NRCo as a mean of settling the debt, thereby triggering the application of paragraph 80(2)(g). If the shares issued in settlement hold no value due to Canco’s insolvency, the settlement amount will be deemed nil, and the forgiven amount will be utilized to reduce CanCo’s tax attributes. Should an outstanding forgiven amount remain after the reduction of tax attributes, 50% of the remaining balance would be included in the taxpayer’s income (100% inclusion required for partnerships).[48]

To avoid 80(2)(g), it was suggested that a subsidiary of NRCo, or its parent corporation, would invest in shares of CanCo so that the debtor could use funds from issuance of shares to repay its debt to NRCo.[49] In this case, 80(2)(g) should not apply because it is a direct transaction.[50] Nonetheless, the CRA could apply the General Anti-Avoidance Rule (“GAAR”), in particular if the operations had no authentic commercial purpose (“bona fide”) and was made principally to obtain a tax benefit.

Deemed Settlement After Debt Parking – Section 80.01

The debt parking rules outlined in section 80.01 were introduced to prevent certain planning involving a creditor selling at a discount to another creditor a commercial debt of a debtor who had a low likelihood of repaying its obligation. The new creditor would then hold the debt, allowing the debtor to circumvent the application of section 80.

For the debt parking provisions to apply to the debtor, the obligation must qualify as a specified debt, the specified debt must be a parked obligation at the time of settlement, and the specified cost to the new holder of the obligation must be less than 80% of the principal amount of the obligation.[51]

An obligation issued by a debtor should be a specified obligation where, at any previous time, its owner dealt at arm’s length with the debtor and did not have 25% or more of the voting rights or FMV of the debtor’s shares, or the obligation was acquired by the new holder from a creditor who was not related to the new holder or the holder claimed a subsection 50(1) bad debt on such obligation.

A specified obligation should become a parked obligation when acquired at a specified cost that is less than 80% of the principal amount and held by a new creditor which does not deal at arm’s length with the debtor or has a significant interest in the debtor. At that time, the obligation would be deemed to have been settled under subsection 80.01(8), as if the debtor had a specified amount in satisfaction of the principal amount of the obligation, and the forgiven amount would be calculated pursuant to section 80(1).

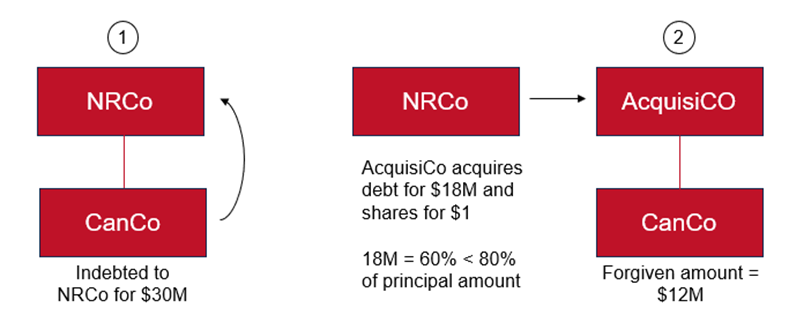

In the first scenario, CanCo is initially indebted to NRCo. NRCo wishes to sell its insolvent subsidiary as well as the debt owed by said subsidiary. AcquisiCo intends to purchase CanCo’s shares and the debt, but at 60% of the initial capital, with the intention of restoring CanCo’s business.

The obligation becomes a specified obligation when the obligation and the shares are acquired by AcquisiCo, because neither entity is related before the transfer. Since the obligation was sold to AcquisiCo (a new creditor not dealing at arm’s length with CanCo) for a consideration amounting to less than 80% of the principal amount of the obligation, a deemed settlement of Canco’s obligation, following the parking of its debt obligation, would be considered at that time.

Consequently, CanCo’s tax attributes could be reduced, and the debtor could ultimately have to include an amount in its income. This can be particularly disadvantageous for the group in the contemplated example above if CanCo had a substantial balance of non-capital losses. Indeed, the change of control of Canco would subject its non-capital loss balance to the Loss Restriction Event (“LRE”) rules contained under subsection 111(5) and would potentially prevent Canco from being able to use such losses against the potential section 80 income inclusion.

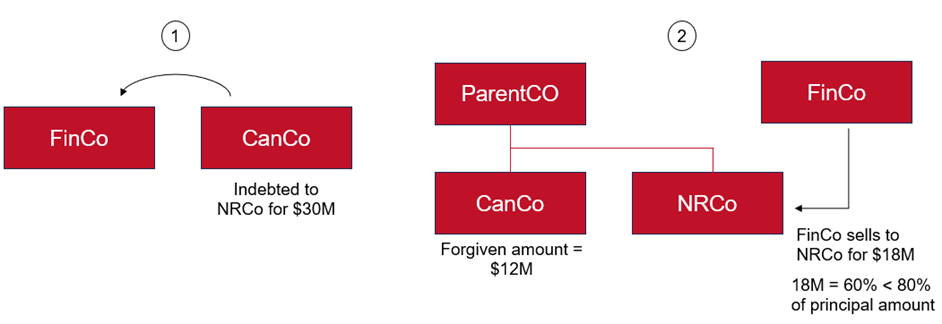

Another example of the application of section 80.01 could be when CanCo is indebted to FinCo, a non-related financing entity. CanCo is facing financial difficulties, and a NR corporation within the group wishes to buy the debt owed by CanCo to FinCo, for a consideration representing 60% of the initial capital.

The obligation already qualifies as a specified obligation because FinCo is not dealing at arm’s length with the debtor. When FinCo sells the obligation to NRCo, who is related to CanCo, for less than 80% of the principal amount of the claim, the obligation becomes a parked obligation and deemed settlement occurs. The same tax consequences as the previous example would apply. It should be noted that if FinCo had transferred the obligation to ParentCo instead of NRCo, the tax treatment would have been the same as 80.01 applies to any parked obligation sold to an entity related to the debtor.

To conclude, Canadian corporations and their NR investors must exercise utmost caution and diligence when planning and executing intercompany cross-border transactions. The prevailing inflationary economic landscape, characterized by elevated interest rates and heightened likelihood of debt default, could trigger unwanted tax consequences, as described in this article. The recurrence of debt restructuring, or other financing transactions undertaken primarily to counter financial difficulties, in an inbound context, will likely increase in the coming months. The potential unforeseen Canadian tax consequences stemming from actions undertaken to try to ease such financially adverse times should be closely monitored, even more so, as the international and Canadian tax landscape is rapidly evolving.

With the prime rate stabilized at 5% since July 2023 in Canada, many economists are predicting a decrease in rates by the end of 2024. However, many others are still skeptical about a return to the historically low rates observed from the post-2008 crisis to the COVID era. The current difficult market conditions will likely affect us for a prolonged period. Therefore, it is important for multinational groups to plan and think ahead in terms of optimizing their financing strategy and capital deployment, from a cross-border perspective, while cautioning not to overlook at the potential related unwanted tax implications.

[1] Statistics Canada,Consumer Price Index: Annual review, 2022, 2023-01-17.

[2] Statistics Canada,Consumer Price Index: Annual review, 2023, 2024-01-16.

[3] Income Tax Act (RSC, 1985, c. 1 (5th Supp.)).

[4] Paragraph 214(3)(a) ITA.

[5] This reduced rate applies only for a shareholder but won’t apply if the debtor is not a shareholder of the Canadian corporation. If the debtor is not a shareholder or is the shareholder but not a corporation, the reduced rate is 15 %.

[6] Subsection 15(2.6) ITA.

[7] 4301(b.1) Income Tax Regulations (C.R.C., c. 945).

[8] Subsection 214(3) ITA.

[9] Ntakos Estate v. R., 2012 TCC 409 (T.C.C.), Mullen v. MNR, [1990] 2 C.T.C. 2141 (T.C.C.).

[10] 4301(c) Income Tax Regulations (C.R.C., c. 945).

[11] Paragraph 17(1.1) (c) ITA.

[12] Canadian Tax Highlights Newsletter, Volume 11, Number 4, April 2003.

[13] Subsection 17(7) ITA.

[14] Subsection 80.4(2) refers to a person “connected” with a shareholder. Subsection 80.4(8) provides that a person that does not deal at arm’s length with the shareholder is connected with that shareholder.

[15] Subsections 15(9), 15(1) and paragraph 214(3)(a).

[16] Paragraph 80.4(3)(b).

[17] Subsection 227(8) and (8.3) ITA.

[18] Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

[19] 247(7) ITA: do not apply when the creditor is a controlled foreign affiliate and paragraphs 17(8) a) or b) apply.

[20] 2003-0033915 – Cash pooling—shareholder benefit.

[21] For example, in the Canada-USA tax treaty, the 5% withholding tax on a dividend is only applicable if the recipient is the beneficial owner and owns at least 10% of the voting stock of the corporation. Otherwise, it’s 15% of the gross amount of the dividends.

[22] IT-119R4. See also 2017-0682631I7 – Subsection 15(2.6)—series of loans and 2015-0595621C6 – Cash pooling and subsection 15(2).

[23] 2007-0253161I7 – Deemed Interest Income on Balance of Sale Due by Non-Resident Corporation.

[24] Subsection 15(2.16) and following.

[25] 2015-0614241C6 – 2015 TEI liaison meeting Q.6—specified right.

[26] Paragraph 40(2)(g)(ii).

[27] CRA Views, Interpretation—external, 2018-0753081E5 – Treatment of losses

[28] Paragraph 248(1)(b)(ii) disposition and paragraph 69(1)(b)(i).

[29] Subsection 15(1.2).

[30] Paragraph 20(1)c).

[31] Paragraph 212(1)(b).

[32] Article XI(1) Canada-US Tax treaty.

[33] Paragraph 212(1)b).

[34] Equity: sum of retained earnings, average of the contributed surplus at the beginning of each calendar month ending in the year and average of the PUC of the corporation at the beginning of each calendar month ending in the year.

[35] Subsections 214(16) and (17).

[36] Subections18(6) and (6.1).

[37] Canada’s transfer pricing rules (i.e. s. 247) mandate that transactions between a taxpayer and a non-arm’s length NR entity be aligned with terms typical of transactions between unrelated parties. Additionally, Canada’s tax treaties, often in accordance with Article 9, may permit adjustments for arm’s-length terms.

[38] A 40% transitional ratio applies for taxation years that begin on or after October 1, 2023, and before January 1, 2024.

[39] Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (“EBITDA”).

[40] Paragraph 214(15)(a).

[41] 2019-0798721C6 – IFA 2019 Q4—78(1)(b)(ii) deemed loan and thin capitalization.

[42] Paragraph (d) of the definition of “excluded obligation” from 80(1) ITA.

[43] The forgiven amount is represented by the difference between the excess of the lesser of the principal amount of such debt and the amount for which the debt was issued over the payment made to settle such obligation.

[44] Subsections 80(3) to 80(12).

[45] Section 61.4.

[46] Section 61.3.

[47] Subsection 80(16).

[48] Subsection 80(13).

[49] 9518785 – Settlement of Debt by Issue of Shares.

[50] IT-293R – Debtor’s Gain on Settlement of Debt.

[51] Subsections 80.01(6), 80.01(7) and 80.01(8).